The Haunting of Tram Car 015 returns to the alternate Cairo of Clark's short fiction, where humans live and work alongside otherworldly beings; the Ministry of Alchemy, Enchantments and Supernatural Entities handles the issues that can arise between the magical and the mundane. Senior Agent Hamed al-Nasr shows his new partner Agent Onsi the ropes of investigation when they are called to subdue a dangerous, possessed tram car. What starts off as a simple matter of exorcism, however, becomes more complicated as the origins of the demon inside are revealed.

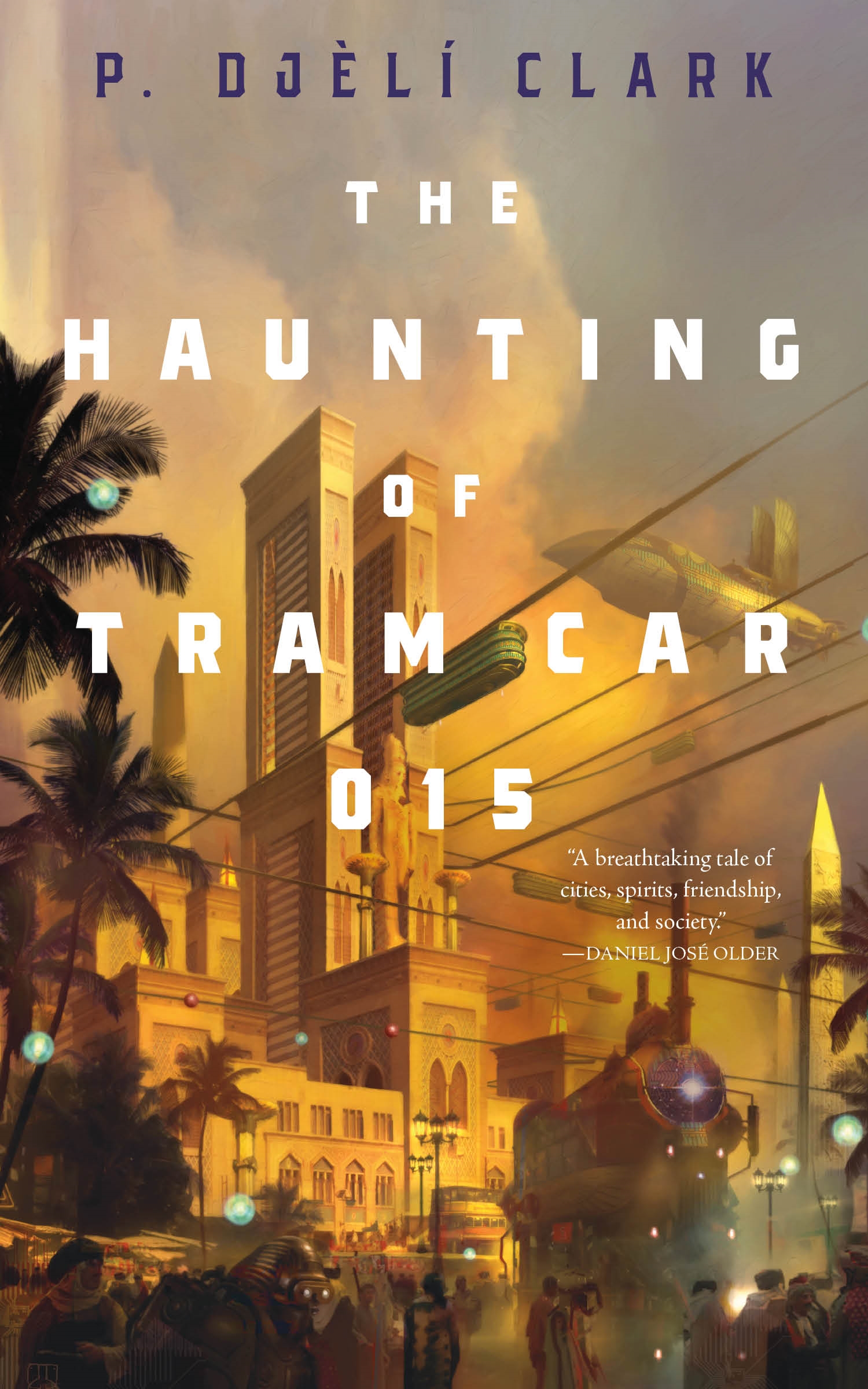

In this story, a couple of public servants are tasked with fixing the problem of a haunted tram car in an alternate-world Cairo. Hijinks ensue. In this world, djinn exist and have helped cement Cairo and Egypt's significance on the world stage, including from a technological standpoint. (The steampunky cover is a pretty good representation of the setting, in my opinion.) Our put-upon agents have to contend with identifying the possibly dangerous being possessing the tram and then have to safely remove it. And all this is set against the backdrop of a Cairo-centred campaign to give women the vote.

I really enjoyed this novella. It was entertaining and fairly amusing the whole way through. Even though I read it in lots of small chunks, I didn't have any difficulty getting back into the story when I picked it up again. I don't think I've read any other stories set in the same world, but now that I know they exist I will keep an eye out. (I have already added "A Dead Djinn in Cairo" to my Pocket reading list, which is actually the only other story I found. If you know of others, please let me know in the comments.)

I highly recommend this novella to fans of gas lamp fantasy and alternate (fantastical) history. Especially if non-European/US settings are a draw. This novella was a great read and, for me, caps off a difficult-to-judge Hugo category.

4.5 / 5 stars

First published: Tor.com, 2019

Series: Yes, other stories set in the same world exist.

Format read: ePub

Source: Hugo voter packet

4.5 / 5 stars

First published: Tor.com, 2019

Series: Yes, other stories set in the same world exist.

Format read: ePub

Source: Hugo voter packet